You may have heard them referred to as “bar-dot” or “dot-bar sights,” or” dot the I sights,” or “lollipop sights,” or even “contrast sights.” You may even know that the technically correct term is “Von Stavenhagen sight.” But do you know why they’re called Von Stavenhagen sights? I didn’t, so I set out to find out why… and learned a few interesting things along the way.

Why Are They Called Von Stavenhagen Sights?

Von Stavenhagen sights are named after their inventor, Georg Von Stavenhagen. Normally, if you want to know something about pretty much any historical figure, it’s merely a matter of looking them up on Wikipedia. But there’s no Wikipedia page for Georg Von Stavenhagen (which is a travesty I may have to personally fix), so just as I did back in college, I actually had to do some research. Most of what I found was in German… and I don’t speak German. So I relied heavily upon Google Translate to dig up details.

Who Was Georg Von Stavenhagen?

I’ve seen Georg Von Stavenhagen referred to as a “German gunsmith” in a few gun forums, but not only is that inaccurate (his family was of Baltic German origin, but he was actually Russian), it’s nowhere near a complete description of this man and his accomplishments.

Born in Russia in 1899 to a noble family, Georg Von Stavenhagen would have been only two years older than the Russian Grand Dutchess Anastasia. He claimed to have met her in his youth when the royal family visited the officer’s school he was attending. As Georg’s daughter Natalie tells it, “They were attracted to each other,” and later, whenever a woman tried to claim that she was the long-lost daughter of the Russian Tsar, Georg would look at the photograph in the paper and say “That’s not her. I knew the real one.”

Georg’s maternal grandfather built his fortune manufacturing war ammunition for the Tsar. His father was a weathly banker in Moscow, but died of Tuberculosis when Georg was nine.

As it did for most noble families, the 1917 Russian Revolutions (Von Stavenhagen would have been 18 years old), turned Georg’s life upside-down. A few years later, he’d fight as part of General Wrangel’s White Army.

But Von Stavenhagen also had an artistic side. After leaving the army and almost dying from hunger and disease, he arrived in Paris and came across the legendary Russian Stanislavsky Theater troupe, where he worked as a stage designer and started to develop an eye for the aesthetic.

In the early 1930s, while living in Berlin, Von Stavenhagen’s artistic interests brought him to photography, where he quickly earned fame for what he’s still probably most famous for: an automotive photographer. Active into the 1960s, his photographs are still sought after and sell for thousands of dollars today. If you search online for “Georg Von Stavenhagen photos,” you’ll see much of his famous work. In their December 2011 issue, German car magazine Auto Bild Klassik did a portrait on Von Stavenhagen, which included many of his most notable photos.

His personal life was even more colorful than his professional one: he was married five times and had seven children by three different women. He couldn’t marry his last girlfriend… because she was already married. So he lived with her… and her husband… until his death in 1978 at the age of 79.

Patenting a New Firearm Sight

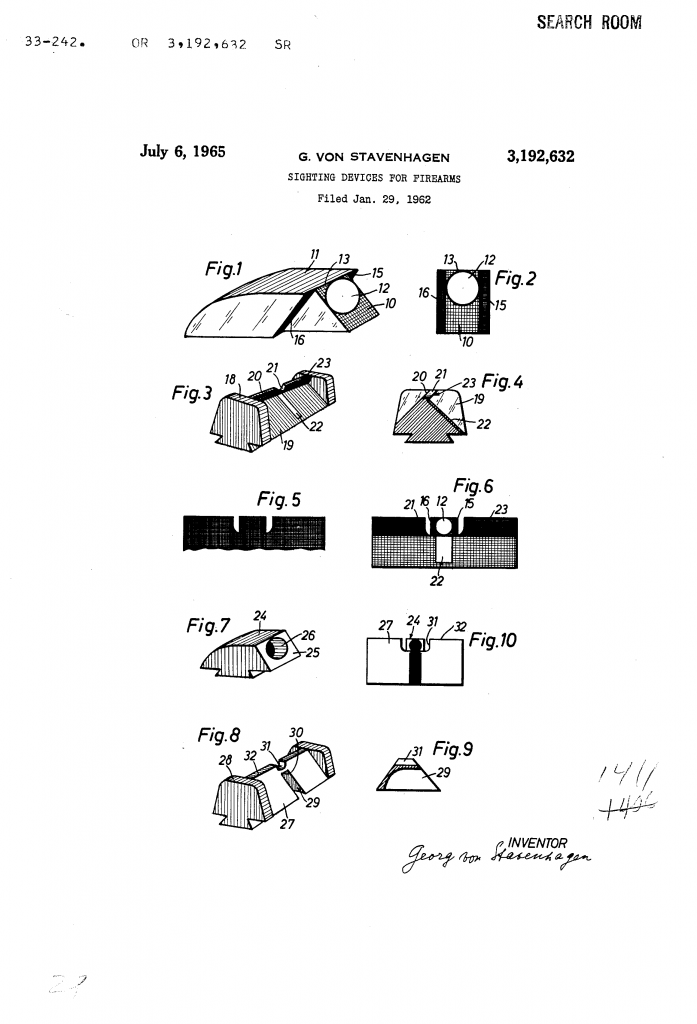

In the early 1960s, near the end of his photography career, Georg Von Stavenhagen turned his attention back to his grandfather’s roots with firearms. His eye for photography combined with his love of things mechanical, and on January 29, 1962 he filed a patent with the US Patent and Trademark Office for a new type of high-contrast sighting device for firearms. This is the original sketch submitted by Von Stavenhagen:

Patent US3192632A was granted to Von Stavenhagen on July 5, 1965 (it would be his only patent). The claims of the patent (which is interesting to read), state:

It is known that the conventional sighting devices are in general only satisfactory with front lighting, whereas in the case of light coming from above or from the back they do not enable perfect aiming, because the apparently grey colour of the sighting device very seldom stands out sufficiently clearly against the colour of the target.

For this reason it has already been proposed to slope the surface of the bead or the bead saddle facing the eye of the marksman steeply upward towards the front and to enamel it white. In another known form of construction the bead or front sight is placed as a solid structure in front of said white surface and beveled towards the rear. In conjunction with this bead a black, upright sight plate With a circular aperture is used. This form of construction of the head is open to the objection that the pistol, when being drawn quickly, catches in the pocket or the like and moreover this sighting device was found to be almost useless in light coming from the front.

In another known sighting device the above-mentioned solid bead is omitted and a black mark painted on the inclined white surface. This avoids the danger of the pistol catching when being drawn but in the event of front lighting the coloured mark was scarcely distinguishable and under other lighting conditions the bead appeared absolutely grey and blurred. In yet another known form of construction a fiat triangular structure was placed upright on the inclined white surface and a backsight leaf with triangular, rectangular or even semicircular notch was used. In this case the bead, when fitted on a pistol, was liable to catch when drawing quickly. Furthermore the former difliculties when sighting could also not be overcome.

As a white mark on the bead with corresponding marking on the backsight plate was of little use in some lighting, it has also been proposed to provide the backsight with a white line at a slight distance from the edge. However, such a thin white line in combination with the remaining thin black edge of the bead was also unable to produce any great advantages. In the case of strong counter-lighting the black corners of the bead and the bead itself appeared grey.

In the case of rear lighting, that is white on white, it was difficult to determine the height adjustment of the bead, All these known bead and notch constructions can be used with top and rear illumination and the bead also stands out sufficiently clearly from the white surface with this lighting, but they are useless in the case of counter lighting. Consequently practically no importance has been given to them and in practice roof-shaped, round and bar front sights are again used in combination with triangular, rectangular or semicircular rear sights, with or without coloured points, squares, lines or rhombs on slightly inclined or upright surfaces.

The invention has for its object to make the front and back sights appear light against dark objects and dark against light objects.

Collaboration with Walther

At the same time he filed the patent, Von Stavenhagen assigned 50% interest in the patent to Fritz Walther, the eldest son of Walther Arms founder Carl Walther. Fritz had rebuilt his father’s company in West Germany after the destruction of the Walther factory in Soviet-occupied East Germany. The implication of the immediate assignment seems to indicate that Von Stavenhagen originally developed the new sight for the Walther P38 being manufactured at that time, which is where the earliest examples of the sight can be found. According to Dieter H. Marschall’s book Walther Pistols, Models 1 through 99:

A shortened version of an all steel WWII P38 may be found from time to time. A capital letter “S” is usually stamped on the trigger guard or next to the “P38” on the slide. These pistols were made (converted) mostly in the 1970s by Mr. Georg von Stavenhagen, a German gunsmith, for special orders from combat target shooters and for private purchase by police and commercial customers.

Here’s a side-by-side look at an early Walther P38 with the original sights next to a P38S with Von Stavenhagen’s high-contrast sights:

P383 vs. P38 front sights

P38S vs. P38 rear sights

Adoption by Other Firearms Makers

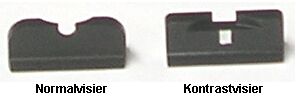

Apparently the license to Walther was not exclusive, because Von Stavenhagen sights eventually became an option on a number of firearms. Among German manufacturers, the original all-black rear sights were referred to as “normalvisier” (normal sight) while Von Stavenhagen’s design was referred to as “kontrastvisier” (contrast sights):

Normalvisier and Kontrastvisier

In addition to appearing on other Walthers like the classic PPK, they can be found on a variety of guns of the period, including West German SIG Sauers:

Von Stavenhagen sights on an early West German SIG Sauer P226

And even though many manufacturers moved on to three-dot sights, some manufacturers, such as Kahr, still ship Von Stavenhagen sights with their current models, such as this Kahr CM9:

Final Thoughts

Now you know not only what the “lollipop” sights are actually called, but why they’re called that and a little more about their colorful inventor, Herr Georg Von Stavenhagen.

His original design concept of vertically-aligned high-contrast sights is still in use today with sights such as the Heine Straight Eights, and even modern three-dot sights like the Trijicon HD or SIG X-Ray use a different color front sight to easily distinguish from the rear sight… a concept that builds upon the original contrast design of Von Stavenhagen.

So the next time someone asks you about those “old sights on a West German P226,” you’ll be able to help tell the story of Georg Von Stavenhagen…

…even though he still doesn’t have a Wikipedia page.

As always, I welcome your questions, comments, and feedback below.